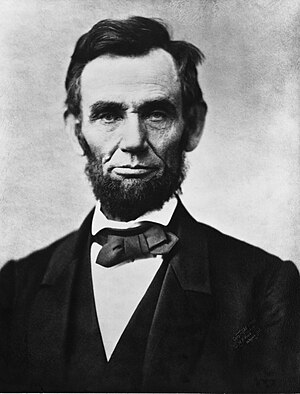

Image via Wikipedia

Last week, I wrote on Abraham Lincoln and the National Economy, part 1: income taxes, the national bank system, and the first U.S. savings bonds. The national banks, along with the new national currency, gave the U.S. better control over their sovereign economy. It displaced the anarchy of individual bank currencies, state bank currencies, and other local arrangements. It also meant that our currency began to have an international value.

There's no question that this changed a feature of international banking--although, it did not necessarily make a huge stir until the 1890's.

There are some other features of international trade, in regard to the "nations vs. markets", where Lincoln exercised "restraint-of-trade" actions. These are what some libertarians and other detractors find against him today.

The first is that Lincoln advocated a strong tariff regime. The second is that he used national clout and diplomacy to restrain trade for the South. The third is that by curtailing political freedom, in regard to the dis-United States of America, he infringed upon individual rights and individual commercial choices about how and where to conduct business.

This post became so long, so I have divided it yet again. This one will be on tariffs. Tomorrow I will post on international trade patterns and the diplomacy that took place during the Civil War. It will also contain my conclusion.

Tariffs

There is at least one author, writing at a libertarian think tank, who calls Abraham Lincoln "The most ardent protectionist in American History." This author cites others of his frame of mind, who say that higher tariffs impelled Lincoln to invade the South. This opinion is hardly new. It was, in fact, the opinion of much of Great Britain, the significant trading partner of the South in cotton and other agricultural products, about the Morrill Tariff of 1861. (The Morrill Tariff was actually signed by Buchanan, but it was enforced and extended by Lincoln.)

Here is a quote from a magazine article in Great Britain (December 1861):

The conflict is between semi-independent communities [in which] every feeling and interest [in the South] calls for political partition, and every pocket interest [in the North] calls for union � So the case stands, and under all the passion of the parties and the cries of battle lie the two chief moving causes of the struggle. Union means so many millions a year lost to the South; secession means the loss of the same millions to the North. The love of money is the root of this, as of many other evils... [T]he quarrel between the North and South is, as it stands, solely a fiscal quarrel.Great Britain abolished slavery in 1833 within its borders, and previously, slave trade in its ships in 1807.

Lincoln was indeed for tariffs. In 1832, in a campaign briefly interrupted by the Black Hawk War, he made this speech, echoing the Whig platform of the time:

"Gentlemen and fellow citizens . . . I presume you all know who I am: I am humble Abraham Lincoln. I have been solicited by many friends to become a candidate for legislature. My politics are short and sweet, like the old woman's dance. I am in favor of a national bank. I am in favor of the internal-improvements system and a high protective tariff. These are my sentiments and political principles. If elected, I shall be thankful; if not, it will be all the same."He did not win that year, but in that district he came in first. And as we shall see, those beliefs stayed with him throughout the remainder of his life.

The difference in tariffs does cut along many of the same lines as the secession of states. There are some differences: the Northeast, with burgeoning industry, was definitely for high tariffs, but the Midwest was not universally for them. On the other side, Virginia was just beginning to industrialize, and wanted some protectionist measures in place for its beginning industry.

Vastly over-simplifying the tariff argument: "Buy & Sell American"

The South had a primarily agrarian economy that had reached economies of scale, (where large producers are able to avoid disproportionate costs--then add slavery as cheap labor to this). They were farming cash crops. The fabric mills to which they sold were predominantly in Great Britain. Therefore, they could do a steady trade back in manufactured goods. Their advantage was to have a low tariff regime for their imports, and avoid a high tariff disadvantage to exporting their cotton or other products. The Northeastern fabric mills wanted cotton exchange diverted to them. A tariff regime made it more likely that Northern states would gain advantages in trade, cutting Britain out. Then Southern states would exchange manufactured American goods for American agricultural products.

Either way, the South was headed for local trade deficits. Their prosperity under the international system did not give a favorable 'balance of trade' to the United States. Each manufactured good they bought had 'value added' manufacturing processes included in the price. In the simplest example, to buy British or Connecticut muslin was to buy their own cotton back, at a higher price. The tariff advocates wanted the balance of trade 'deficit' to be internal rather than external. It would strengthen the national economy, if not primarily the South.

Add to Northeastern frustration that the distribution and shipping between Southern ports and British ones was well-established, while railroads from South to North were not. Thus, when Lincoln urged Congress to pass his Banking Act of 1861, he mentions fundraising not just for war, but for building railroad infrastructure to the South.

A Whig Party Legacy

The "system of internal improvements" was a philosophy that was made Whig doctrine by Henry Clay. In it, he maintained that monies from tariff should be dedicated to developing domestic infrastructure, such as railroads, to aid in interlocking domestic economy and expanding it Westward. Lincoln was a Whig before that party dissolved. The Republicans of that time took on much of the Whig policy. Lincoln did not deviate from it.

From Lincoln's point of view, tariff had the advantages of funding internal improvements and funding his army. But Lincoln did not break the South economically through tariffs. He did it through blockade.

References:

Lincoln: Speeches and Writings, 1859-1865. Library of America. Available.

Civil War Home, using the Macmillan Information New Encyclopedia, linked above and here.

Shelby Foote, The Civil War: A Narrative, Volume I. Random House. Available.

The Miller Center, University of Virginia: Abraham Lincoln, part 5, linked above and here.

The Union Pacific Railroad, Lincoln and the Railroad, here. Is that restraint of trade?

William Wunder, The American System of National Republican and Whig Henry Clay, above and here.

No comments:

Post a Comment